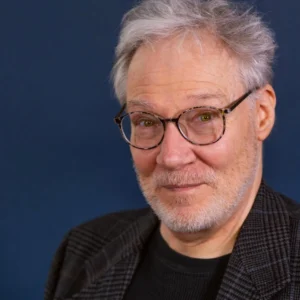

This week I listened to a podcast that had me grinning and nodding through most of its 53 minutes. In Season 2, episode 3 of the Telepathy Tapes, Ky Dickens explores the nature of creativity and inspiration with special guests author Elizabeth Gilbert, music producer Rick Rubin, and showrunner Liz Feldman. (You can listen to it here or anywhere you listen to podcasts.)

[T]he concept of a download coming all at once is well documented in literature. Take for instance, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. She described in the book’s introduction, having a waking dream, and she said the story appeared to her whole. And director James Cameron said the idea for Terminator came to him in a dream while he was sick in Rome, he saw the image of a metallic figure emerging from fire, and that single image became the basis of the entire franchise.

–Ky Dickens, Telepathy Tapes, Season 2, episode 3

Ky and her guests discuss their experiences with inspiration. Their questions include: What happens if you don’t act upon an idea, does it leave you? How do artists, inventors, and thinkers come up with the same ideas at the same time on opposite sides of the world? Do places and families have creative spirits that are passed on from one person to another? How do we surrender to inspiration while maintaining the discipline of practice? What is the relationship between creativity and anxiety? Can creativity be the secret to a happy life?  Never have I heard or read something that captured so many of my own personal beliefs and experiences of creativity in one place, and like so much of Ky’s work, the episode is well-made, brave in its vulnerability, and compelling. Ky is a natural storyteller, as well as someone who is a connector, attracting people from many disparate corners of the world to bring them together to collaborate on really important ideas.

Never have I heard or read something that captured so many of my own personal beliefs and experiences of creativity in one place, and like so much of Ky’s work, the episode is well-made, brave in its vulnerability, and compelling. Ky is a natural storyteller, as well as someone who is a connector, attracting people from many disparate corners of the world to bring them together to collaborate on really important ideas.

There are writers who love to write, and writers who love to have written. I’m the former. I love the act of writing. When I am writing I feel as if I am doing what I was meant to do. I lose myself in the flow, time stops, the world fades, and I am immersed in the art of creation. It feels like a gift, like tapping into something greater than myself. I am filled with gratitude after completing a story or a poem, and I am happy to let it go into the world and work on the next thing. The practice of writing is for me like prayer or meditation or magic.

There are writers who love to write, and writers who love to have written. I’m the former. I love the act of writing. When I am writing I feel as if I am doing what I was meant to do. I lose myself in the flow, time stops, the world fades, and I am immersed in the art of creation. It feels like a gift, like tapping into something greater than myself. I am filled with gratitude after completing a story or a poem, and I am happy to let it go into the world and work on the next thing. The practice of writing is for me like prayer or meditation or magic.

I believe that we are all called to find the unique ways we can co-create with the Universe.

These questions about inspiration and making art are why I decided to write the Mother Christmas trilogy. It’s as much a story about the Muses as it is about Saint Nicholas. The idea for the Mother Christmas story came into my head like one of the downloads that Ky Dickens talks about in her podcast. The majority of that story arrived fully formed more than twenty years ago, and it took that long for me to be introduced to Vic Terra, the artist living in Brazil who was meant to illustrate it. A lot of life has happened in the last two years to put the writing of Volume Two on hold, but I’m hoping to get back to it again in earnest. I’ve been getting nudges in that direction, that it’s time to prioritize the work.

However, before Mother Christmas, I wrote another very short story, “Shower Muse,” first published in 2015, in Scheherezade’s Bequest Volume 1, Issue 2. That story has a lot to do with inspiration and acts of creation. It has only appeared in print, and this felt like the right time to share online.

It’s a quick read at 825 words, and I hope you enjoy it. It’s also another story that came into my head fully formed… yes, in the shower.

***

Shower Muse

They told Delphine she couldn’t be a trickster.

“You are a Muse, and you should be proud,” said her mother, whose own calling was terpsichorean.

It was made worse somehow by Delphine’s aqueous preferences. Having grown up near the sea with Poseidon’s daughters, Delphine was drawn to the water. At first, her mother was enthusiastic, citing the great painters and poets who found inspiration in the sea. But Delphine wanted to tempt and tease, not lead and motivate.

Again Delphine’s mother put down her elegant foot, “Your calling is to inspire greatness, not perform pranks.”

Delphine never saw the difference, not really. She went to Apollo for help, but her uncle only patted her on the head and said, “Find a way to make it work, child. You are what you are.”

With mischievous delight in her heart, Delphine settled on writers and chose the shower as her modus operandi. She would feed them new ideas as was expected of her, but only when they stepped over her oracular threshold and under the stream of water.

Her traditionalist mother was suspicious, but Delphine argued fiercely that it was a modern twist on a proud legacy of Muses who dwelled in sacred baths and holy wells.

As droplets fell over their eyes and lips, Delphine whispered sonnets, stories, and screenplays into the writers’ ears. She delighted in the way they scrambled for soon-wet pads of paper, dropped devices down into puddles, and jotted words on steam-covered glass.

Sometimes the inspiration stuck, but most often it faded away as the writers grabbed their bathrobes, or busied themselves with brushes or creams. The seeds she planted would drift like dandelions into the realm of dreams, now and again revisiting the writers in sleepy reverie.

When scolded by her mother, Delphine argued that even the most fleeting of poetry could still be divinely inspired.

“An epic that exists for but a moment is not unlike a rose that begins to die when cut,” Delphine argued, grinning as she watched a playwright trying to write the idea for a brilliant comedy on her arm with wet eyeliner.

Eventually Lisovyk, trickster God of the forests, took notice and leapt across pantheons to have a word with the precocious Delphine.

“You are serving neither the Muses nor the Lords of Shadow and Misrule,” Lisovyk said, causing dandelion seeds to rain upon Delphine’s head and grow from her hair.

She shook them off and dismissed his warning, wandering off to continue her work. Lisovyk decided to teach her a lesson. He took sand from the beach and sculpted a perfect soulmate for Delphine. Lisovyk then used his magic to lead Delphine to the seashore, where the two would meet. Satisfied, Lisovyk hid to watch.

The couple instantly connected and spent hours sharing their passions. When the chariot of the dawn appeared in the sky, they sat entwined in an embrace, and as they prepared to welcome the morning with a kiss, Delphine’s soulmate broke apart into grains of sand that were swept away into the sea. Delphine sat in disbelief as Apollo lit up the world.

Still smug but slightly rueful, Lisovyk left Delphine to mourn and consider his lesson.

After time passed, Lisovyk returned and asked Delphine if she would continue to torment the writers with her fleeting inspiration.

Delphine looked at him and smiled while slipping a villanelle into the mind of a young poet shaving her legs. “I thought I might have you to thank for that night,” she said.

Lisovyk was puzzled, “Didn’t you learn about the cruelty of things that do not last?”

Delphine smiled, watching as the poet tried to write with shaving cream on the wall. “You actually helped me to better understand that my instincts were right all along,” she said. “In a way, you proved me right.”

“My gifts to the writers are twofold,” she went on to explain, “I first show them what is possible. If they have one good idea, they can have another.”

Lisovyk watched the young Muse’s face light up with conviction, and he felt something rise up in his throat that hinted at regret.

“Secondly, I’m teaching them a lesson about procrastination. When it comes to creativity and the imagination, the divine gifts are fleeting. If a writer does not act upon them, they will be lost.”

Delphine turned her attention to an aging novelist who was listening to the radio in his shower. She teased him with a snippet of an unforgettable character, then turned her attention back to Lisovyk, “Too many dawdle away their time, make excuses, seek distractions. It’s like closing your eyes to a sunset. Another one will come along, if you live to see it, but it will never be the same one.”

Lisovyk skulked away, then stopped under a waterfall to cool down. As he stood under the rushing waters, inspiration rained down upon him, and Lisovyk laughed.

***

On February 1, we reach the halfway point between the winter solstice and the spring equinox—the Celts called it Imbolc, and it’s the season of renewal. The wheel turns, and today marks another year, another birthday for me. We are irrevocably tied to the movements and rhythms of this planet.

On February 1, we reach the halfway point between the winter solstice and the spring equinox—the Celts called it Imbolc, and it’s the season of renewal. The wheel turns, and today marks another year, another birthday for me. We are irrevocably tied to the movements and rhythms of this planet.